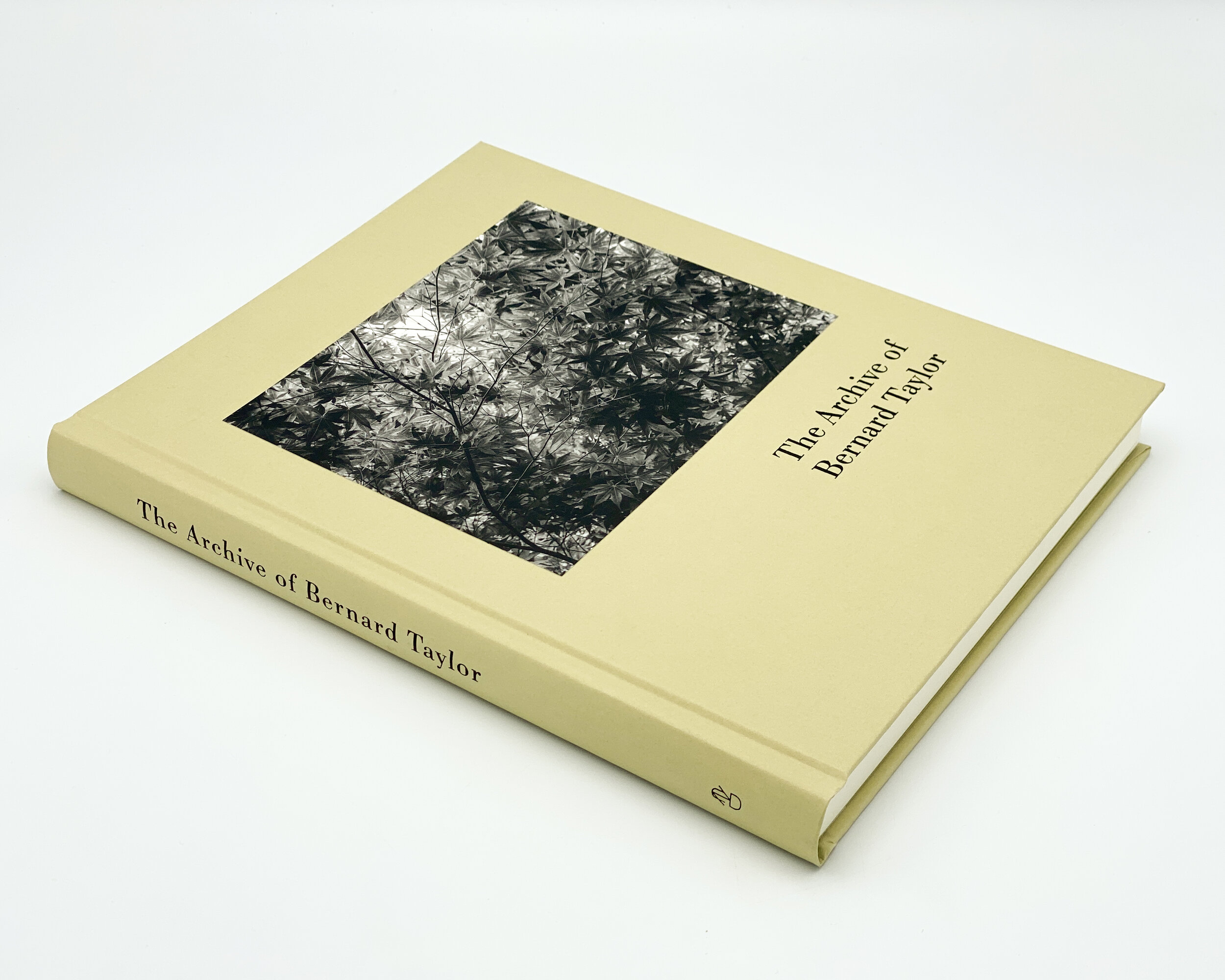

The Archive of Bernard Taylor

In his preface, filmmaker Peter Ward describes acquiring the archive of Bernard Taylor, an enigmatic former resident of his suburban New York village. Ward selected and edited this group of Taylor’s papers: intimate worksheets that combine a series of photographs, maps, and postcards with illusive short texts that were clearly created for Taylor’s private study. Ward’s editorial interjections – all relating to local history – punctuate the book, and blur distinctions between fiction, biography, and reportage.

An afterword by The Publisher contextualizes Taylor’s worksheets, critically re-examines Ward's editorial practices, and describes the agonizing process of preparing this edition.

The Archive is equal parts photographic narrative, puzzle and mystery – an obstructed view of an inward journey that explores the outside world. The questions and answers remain with the reader to piece together.

The first edition of The Archive of Bernard Taylor included this preface by the editor Peter Ward. It is included in the Understory edition and reproduced here to help contextualize the book for the curious.

— The Publisher

The editor's preface to The Archive of Bernard Taylor

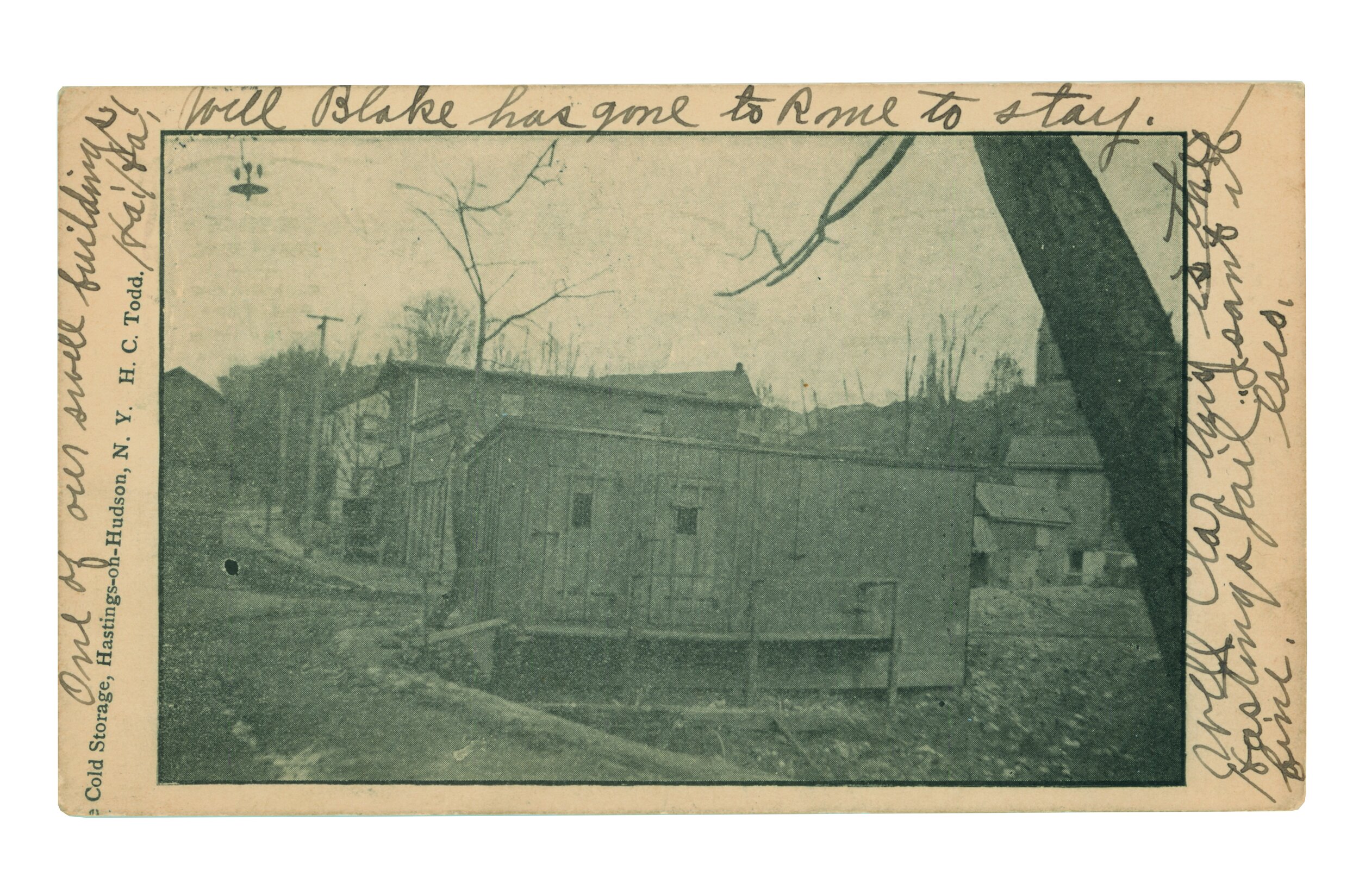

I have lived in the suburban village of Hastings-on-Hudson, just a few miles north of New York City, for two decades, but I had no contact with Bernard Taylor until I attended the sale of his personal effects soon after his death. In fact, only a few older residents seem to have met him, and tell me that he had kept mainly to himself after he moved here in the 1950s. They recall seeing Mr. Taylor walking through Hillside Woods, or along the Old Croton Aqueduct trail, though only in the early morning hours. It is clear, however, that the pictures in his archive were made at all times of day, and not exclusively in Hastings, proving once again that you can rarely rely on people’s recollections.

A local estate liquidator neatly laid out his belongings throughout his home near the elementary school. The house itself had an aura of mystery. From the front, it was a drab mid-century ranch, but growing from the back was a large contemporary addition that served as Mr. Taylor’s library and study. It was there that I found six boxes crammed with papers in varying degrees of preservation. Newspaper and magazine clippings, typed or handwritten notes, and pictures filled hundreds of folders. All of the photographs, postcards, and texts included in this book were found in these folders.

Years ago, while in college, I worked in the library sorting archival material that had been donated by alumni. I enjoyed looking through someone else’s life and trying to put some order to what remained of it. Discovering Mr. Taylor’s work rekindled these old excitements. I was able to buy the whole group for forty dollars, a trivial price compared to the diversion I knew it would give me. My wife and sons thought I was a fool for buying these “old scraps,” but I have loved looking through them over the past few years, and organizing them has been an illuminating experience.

You will discover that Mr. Taylor had a passion for trees, but also that he seemed to be in constant pursuit of something to photograph. I wonder what forces compelled him. A neighbor told me she believed he had worked as an editor at a paper in the 50s and 60s but I could not find any record of that.

There is something about living in the suburbs that I can’t quite define. Mr. Taylor was far older than I – there are two generations between us – and yet I feel a shared experience. Many of the places found in his photos have changed since he was here, but can be recognized easily. In fact, you can use them to follow in his footsteps in a walk around the village. And I think all will agree that there is a quaint poetry to the texts he typed and pasted next to many of the images.

There is also a haunting quality – like rain on a sunroof, the inside dry, the outside speckled with fresh drops, the pane of glass holding these two worlds, warm and cool, exposed and sheltered, sharing and dividing. I know I’ve read some of these words before, but I can’t place them, and in truth I am not qualified to provide literary analysis. I prefer to let this work stand on its own, and present it as a view into one person’s experiences, in one place, in one life.

While I tried to leave the papers as I found them, I of course had to put them in an order I thought made sense for a reader. This is a personal selection, and I am sure it leaves me open to criticism. Certainly someone with more knowledge of the material would chose a different series and sequence. I can only ask for this book to be accepted as it is, and hope that what is here reveals enough.

If anyone knew Bernard Taylor and has information about his life and work, I would love to hear from them. Perhaps we can collaborate on an improved second edition.

— Peter Ward

The Publisher's afterword to The Archive of Bernard Taylor

As a complement to the editor’s preface we posted for those curious about the contents of The Archive of Bernard Taylor, we share The Publisher’s afterword to the Understory edition.

The few readers of the first edition of this work peered into the intriguing world of a certain Bernard Taylor. The circumstances that led to publication were, it was obvious, impeded by the timing of the editor’s research (and the apparent desire to rush it into print), the unattributed authorships of the texts within Taylor’s so-called worksheets, and, at the risk of being cruel, the lack of clear and focused editorial practice by Peter Ward. That edition – published privately in a tiny run of 50 copies and given only to friends and family – slowly slipped out into the broader world, was seen by various readers, and then subjected to more intense scrutiny.

First there were the debates over the existence of the worksheets, then the authenticity of their contents. Mr. Taylor does seem to have existed in Hastings-on-Hudson for many decades (he paid village taxes, it is believed), and his photographic record of the village is not questioned: the places are easily located. Why, after all, would the editor create an elaborate scheme to conjure a series of images, build a textual architecture around them, and then deflect attention with a series of editorial interjections that are all verifiable with historical documentation? One does question, though, why Peter Ward demonstrated an understanding of contemporary research tools, and yet neglected to apply them to each and every one of the worksheets he included.

I am told that Ward worked as a documentary filmmaker, and he is listed as the cinematographer for a number of videos made by experimental musicians. He did live in Hastings and knew Tom Lecky, who is mentioned in his text. So again, why concoct such an identity for the sake of fake-exploring another? Ward mentions a wife and two children. Perhaps a copy of his book will one day inspire one of them to come forward with details. Admittedly, details would be a welcome addition to this fascinating, but frustrating, enterprise. I am left with the belief that if one spends part of a life on the outside looking in, it is equally plausible that another part of that life is spent on the inside looking out. It is too bad that in this case the windows are so dirty.

I entered the story two years after the publication of the first edition while visiting Tom Lecky in New York. Tom handed me his copy without explanation or context and observed as I looked through it. I am sure he knew the effect it would have on me, that I would recognize many of the authors of the texts, and that it would fascinate me. He gave me a photocopy to take away.

When asked about the background of this curious book, and why it was presented in this way, Tom said, “I let Peter go down his own path with it and didn’t ask questions. He asked me about the aquatints and the book description, and showed me a few images to see if I knew their locations, but Peter never showed me all that he had. I gave him his space to play with it. But when he handed me a copy of the completed book, I was pretty shocked at what was there, not to mention what wasn’t there.”

What wasn’t there. To say that Ward had a light touch as an editor is a grave understatement. Yet these absences engrossed me. The more I annotated my copy, the more I developed the threads of the writing and the structure of it all. My photocopy overflowed with notes, identifications, amplifications and corrections. Preparing a new edition – which Ward essentially begs for in his book – would develop Bernard Taylor’s work, delve deeper into his various interests (obsessions?), and contextualize his worksheets. Wouldn’t readers want to know that Taylor was not the author of his disparate quotations? Didn’t they deserve to learn that these were the words of Stein, Emerson, Thoreau, McCarthy, Roussel, Heisenberg, Cather, Rand, Pasteur, Munari, Tanizaki, Alpers, Callahan, Hval, etc., etc.?

The designers and I worked on various formats and models, compiled indices and appendices. We even tried to source a paper that we thought would replicate the heavy cardstock we were told was used as the original mount for the worksheets.

But nothing spoke like the original book. Peter Ward’s creation left a trace that resisted our intervention. And I could not bring myself to undermine the experience of those glimmers of recognition, followed by frustrated incomprehension, that I felt upon first seeing it. Tom told me that Ward moved from Hastings four years ago (which we also learned in the chapbook of material not included here that was published around the same time). Ward has not stayed in touch. The center of this thing is, literally, somewhere else.

So in the end I decided that this new edition should merely reproduce Ward’s original book, free of any changes. It is a facsimile of a phantom.

In what may be my greatest mistake as a publisher, I have left it alone, and I ask you to forgive what I feel compelled not to explain.

— The Publisher